When your piano playing doesn’t sound right, ask yourself: “have I analyzed the music?” Music analysis is the process of coming to understand the music. This may include a formal musical analysis, such as with Roman numerals or a Schenker graph. However, it may also include simple, common-sense answers to the basic question “what features do I notice in this piece?”

In this article, I will explain why you should analyze music, and give you some practical suggestions for how to analyze music.

What is analysis?

Music analysis serves at least two purposes:

- To understand what the composer wrote.

- To understand what the piece means to you.

In my opinion, Purpose 1 is not about morality. As far as I am concerned, you are under no obligation to care about what the composer wrote. However, it may be of use, as it can help you understand the work as a whole.

Regarding Purpose 2, I generally try to follow a rule: “If it doesn’t mean anything to me, it’s not real.” If there is something in the score, I do not take it seriously until I can convince myself that it really should be there. Otherwise, I try to ignore it. There is no sense in insisting I play a passage forte if I don’t see what is motivating that forte. Otherwise, what will move me to play loudly?

How is analysis different from performing?

Performing, in contrast to analysis, is not about understanding, but rather about doing.

I want to make a few points about performance.

Performance is always “correct.”

Your performance is always a correct rendition of your analysis, in the sense that you are always playing the piece as you see it in the moment that you are playing.

This is not just a philosophical point. You don’t need to play the analysis. You only need to perceive the features of the music, and then play the music, not the analysis.

Before you perform, talk through the analysis if you want, but don’t try to play the analysis. If your analysis isn’t right, change it. If you can’t play the analysis you have written down on paper, the problem is with your focus or with your technique, not with your performance. This attitude will free you from trying to control things over which you have no control during a performance, and it will make it much easier to let go of past performances that did not go well.

Performance requires mindfulness.

It does not matter how well you “know” the music, or how well you “can play”. What matters most is how present you are. This can vary day-to-day. Many problems which appear to be problems with understanding of the music, or with technical ability, could be better understood as problems of distraction or of lack of commitment to doing one thing at a time. That does not mean they are trivial; these problems are just as difficult to solve as are more conventional musical issues.

Performance requires acceptance.

Just because a performance is always perfect does not mean you will always feel great about it. You will make mistakes. You will be uncertain about your analysis. You will misunderstand things in the score and your teacher may reprimand you for that. Performing music requires accepting these possibilities.

Music Analysis: A Step-by-Step Example

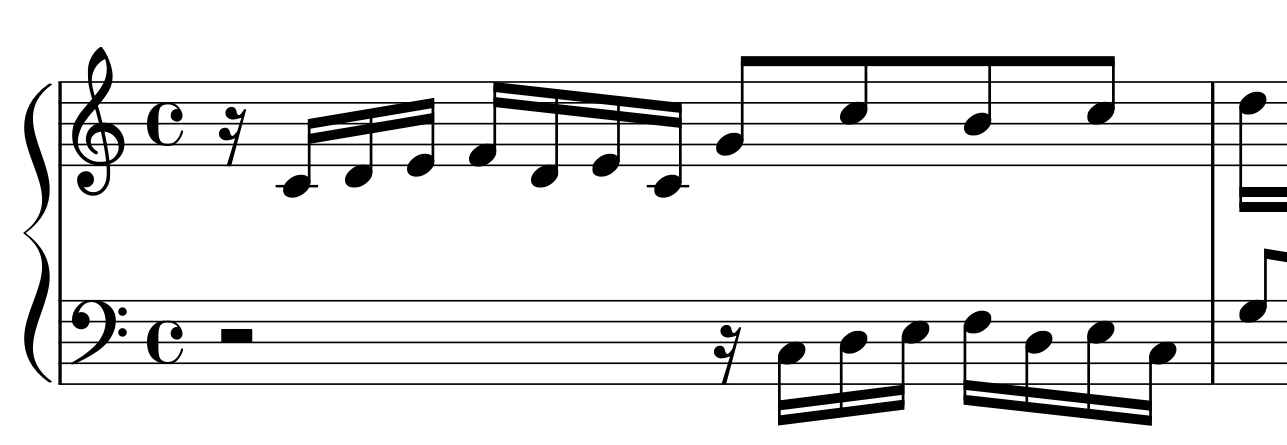

I’d like to illustrate some points about analysis by taking a look at Bach’s Invention No. 1 in C major.

The analysis of music consists of observing features of the piece. I have given some diagrams which I hope will illustrate the features I have observed. Accompanying the written analysis is a sequence of videos in which I demonstrate the features I have observed.

Main idea: The point is not to be artistic. It’s to observe features and notice how they are implemented mechanically.

This connection between the musical and the mechanical is vitally important. I believe a practice should, overall, be much more mechanical than most teachers recommend. You must have a clear understanding of the physical movements you will use to execute your musical ideas.

This understanding, however, is not something you should pursue while performing. In the moment of performance, you rely on artistic impulse to carry you through, simply reacting to the moment. We practice mechanically so that we can react musically.

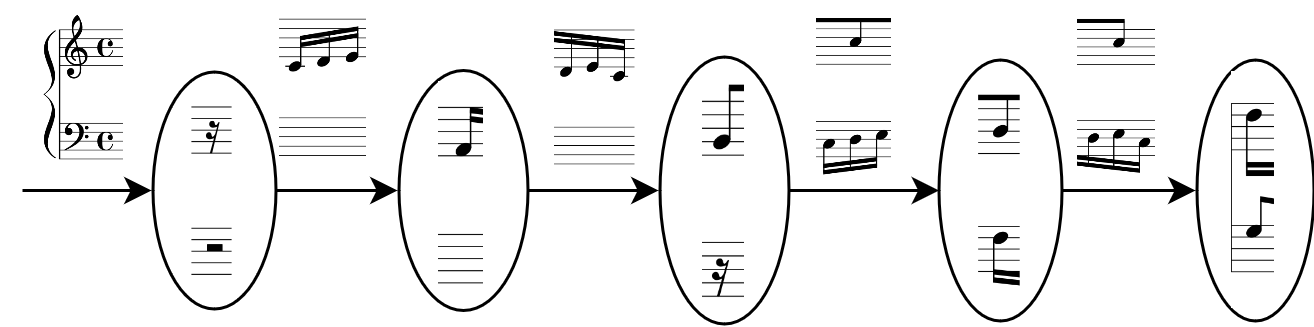

I am aware that the diagrams may look confusing at first. If you don’t understand, listen to the examples, and make sure you read the text. I want the diagrams to make things simple, not complicated. The point of the diagrams is not to introduce a formal system of notation. They are meant to be visual representations of my intuitive understanding of the music. The purpose is only to show how a piece of music can be understood as doing one thing at a time. Notice how they are all chains of events, one after the other.

So, let’s get started.

1. Make sure you understand where the beats are.

The purpose of this stage is to develop rhythmic flexibility. It is not to play expressively, or to understand any aspect of the music other than the beat, and how to play the right notes at the right time. If you have problems playing correctly, or in tempo, try the waterfall technique.

Musical interpretation is primarily a matter of arranging the beats how you want them.

It’s not about sound, it’s not about notes, it’s not about emotion, it’s not about articulation, it’s not about expression. If those concepts work for you, do them, but I believe a lot of extremely common problems are neatly avoided by looking at it in the way I’m suggesting.

Example:

The time signature is 4/4, so let’s say a quarter note is one beat. This isn’t a final decision, and my aim is to remain as flexible as possible. But, let’s go with it for now.

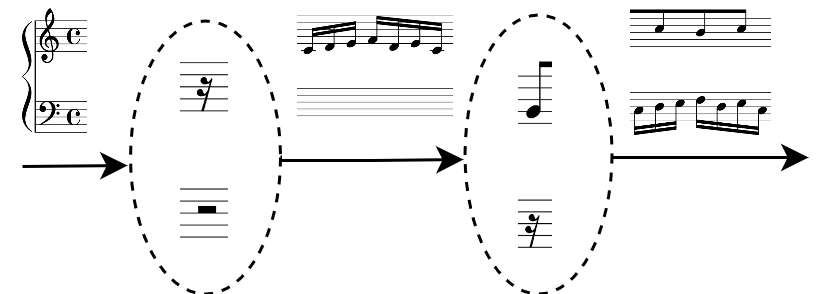

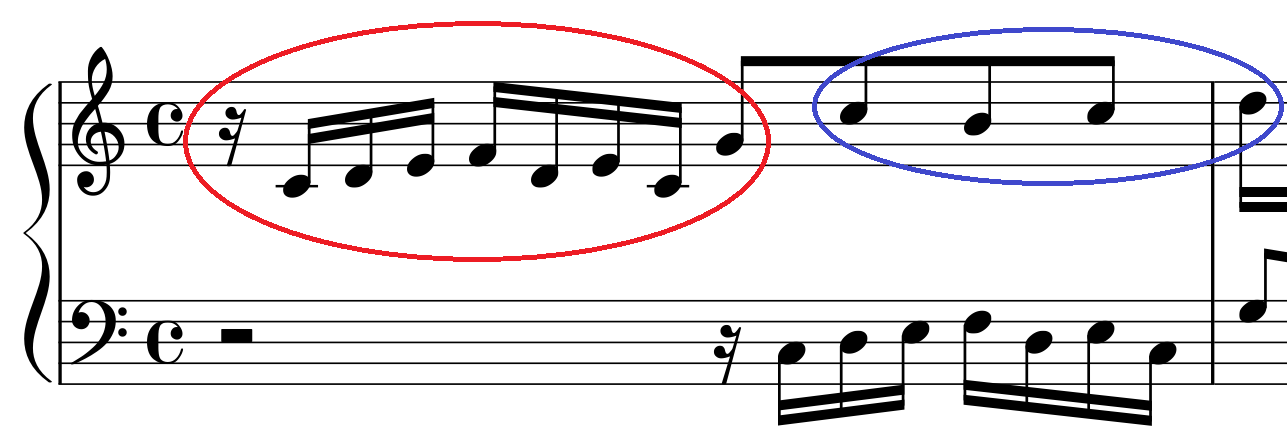

Let me take that first measure (plus the downbeat of the next), and really visualize those 5 beats.

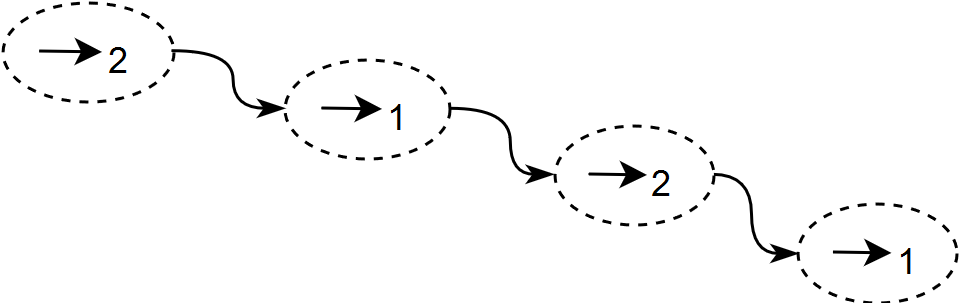

I have circled the notes that fall on the beats, and connected them with arrows showing the notes that lead into the beats. Each beat, therefore, consists of these two parts. By doing this, I can conceive of this measure of consisting of 10 actions, one leading into the next.

Just looking at the quarter note beats:

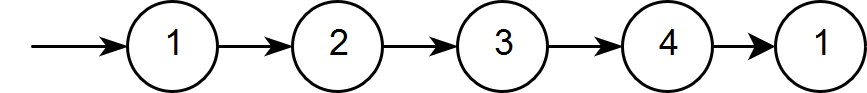

If I number the beats, we can simplify the visual representation even further.

This is one measure of music, plus the downbeat of the next. This is, in some sense, what I see in my mind’s eye when I hear one measure of this piece. It’s a complete object, something I can touch and manipulate. My understanding of the music is based on arranging these simple objects in the order in which I want them to be, and on clarifying the relationships between them. It’s not about sound. The sound is only an expression of this basic structure.

The diagram is only an illustration. The actual music is more complex than this, even in my mind. But, it will serve to demonstrate some points.

Half note beats:

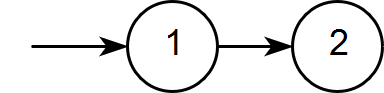

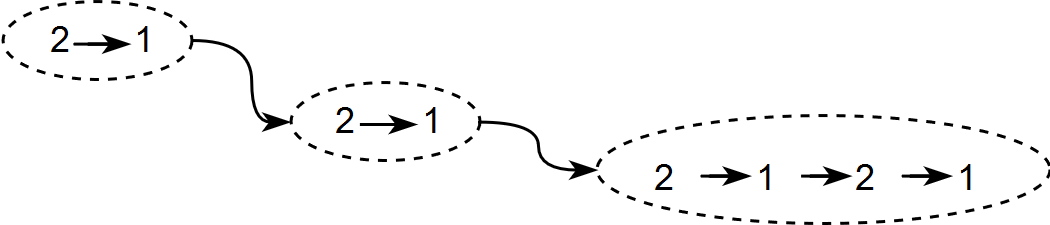

Now, suppose we wanted to consider the half note as one beat. Grouping every two quarter notes together, the diagram might look something like this:

This basic abstract figure could be made more concrete by putting the music notation back in place:

And it can be made even more abstract by removing the quarter note beats entirely:

Eighth note beats:

Given that I am trying to be flexible with the beat, I’d also like to try playing with the eighth note as the beat, and the sixteenth note. The measure, represented as eighth notes, might look something like this:

The video below demonstrates several of these possibilities.

Depending on your purposes, any of these could already be an acceptable rendition of the piece. If you cannot play correct notes in tempo at this stage, it is vital that you work that out before going further. All other stages of analysis and interpretation of music depend on the fact that you have a clear concept of where the beats lie.

Important point:

I want to made a point regarding the selection of which note value gets the beat. I don’t believe there’s is any right or wrong here. I’m experimenting to see what I prefer. It is not essential that you try each and every one of these options. If you know what you want, just go for it. I’m trying all of these because I enjoy the creative process, and the hunt for new possibilities.

3. Look for cadences and phrases.

A next step may be to look for phrases, which are a larger unit than the beat or measure. Often, the easiest way to find phrases is to look for cadences, which serve as punctuation marks.

If you have taken a music theory class, you might be worried about misidentifying cadences and phrases. This is the danger in taking music theory classes. In practice, don’t concern yourself with this. Just notice what jumps out at you. If it’s wrong, you can always fix it later.

Example:

In the previous video, you can see that I am able to play all the notes. And you may even say there’s some expression, but that is not my concern. The performance is perfect, as all performances are. If I want more, I can analyze further, and work to incorporate that analysis of the music into my playing.

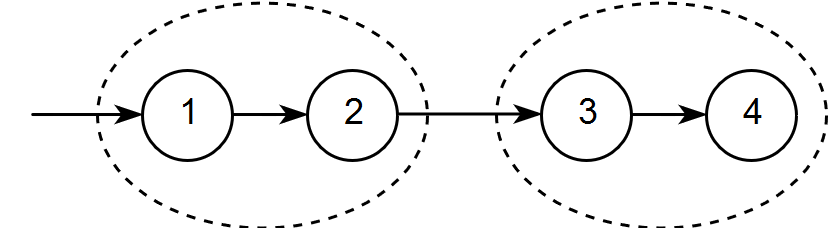

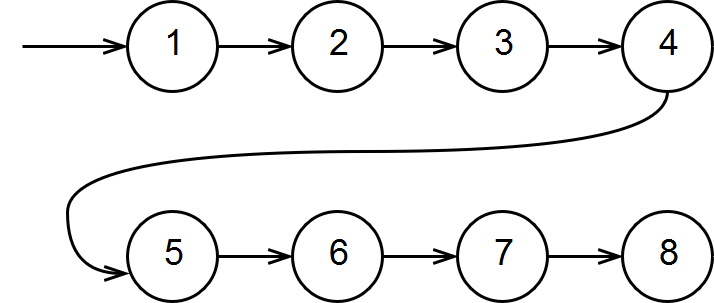

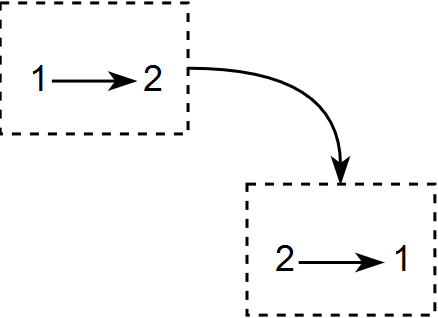

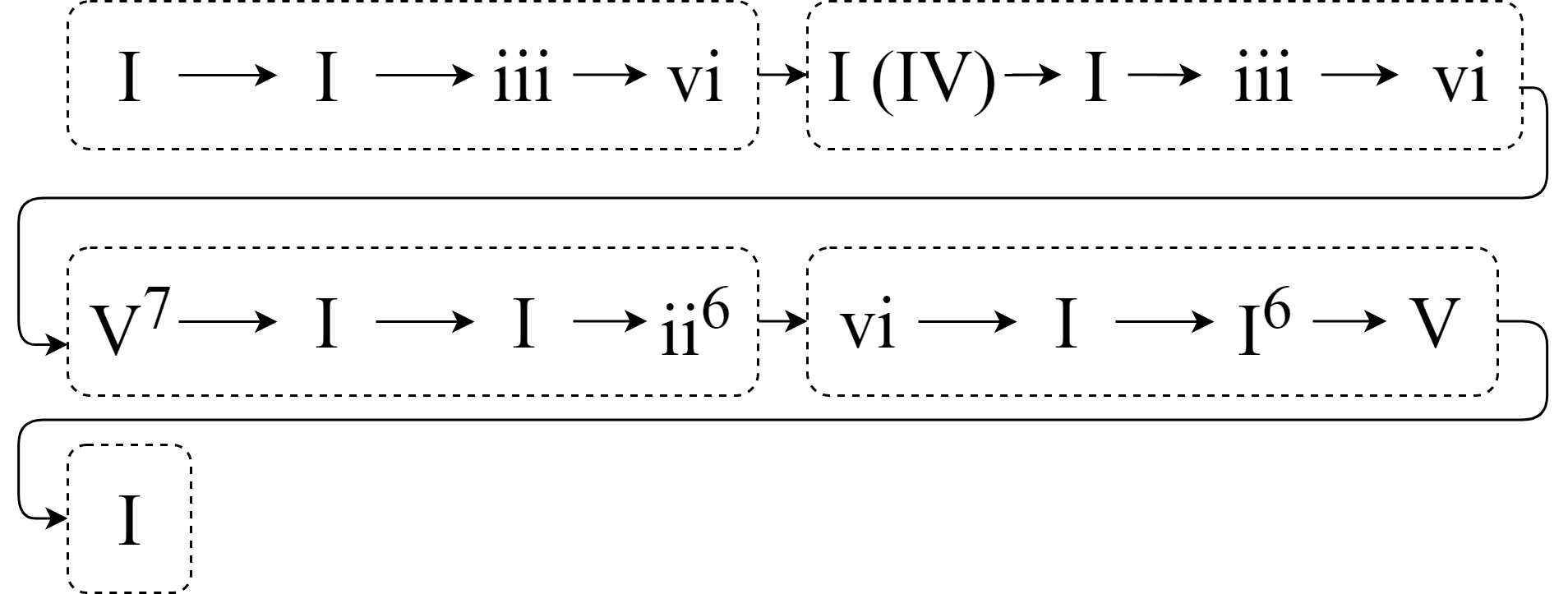

I notice cadences in measures 3, 7, 15, and 22. Let’s look at the phrases ending on measures 3 and 7. We could diagram them as follows.

Since the half note is the beat, each measure consists of two half notes, strung together with whatever material Bach has chosen.

Or, perhaps we don’t even want to consider the content of each measure, but simply observe how they flow together to create a whole phrase. Do you see how each phrase is a single object? How the measures are objects? How they are connected together?

I demonstrate some of this in the video. My task is to get a sense of the phrases as structures. I’m not trying to express anything. I am only trying to play with them, like a child playing with clay.

4. Untangle the counterpoint.

A study of Bach would not be complete without some mention of counterpoint. This could have been done earlier, but it doesn’t really matter. Counterpoint is complex, and requires immense focus to execute properly.

Don’t worry about understanding everything. Label what you observe. Notice how things fit together. Over time, your internal concept of the piece will crystalize. You are building a structure which has both simplicity of form, and also richness of detail. This doesn’t happen overnight, but as it happens, it becomes part of you.

Example:

Motives

First, I will look for motives: small fragments of melody that have their own integrity, often repeated throughout the piece. I’m not concerned about finding each one, just enough to keep me interested. Let me repeat myself in saying that I am not really looking hard for anything, but rather categorizing the features of the music that have already jumped out at me. This isn’t a music theory term paper.

In the first measure, I see two motives. Perhaps we could call them a “subject” and a “countersubject.” Or we could call them “Tom” and “Sue.” It’s totally immaterial, because these are only labels, and what I am really concerned with is seeing them as objects, anyway.

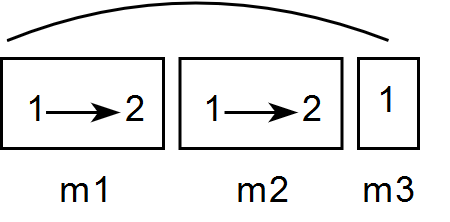

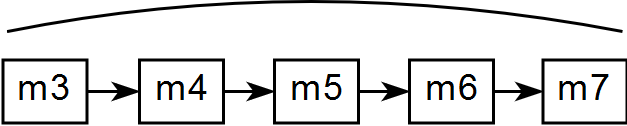

The first motive is two beats. Thus, we could diagram it simply as two beats:

This is a complete picture of the motive. What I play is not one note followed by the next, but rather one beat followed by the next. This is the structure which will be used to express my emotional reaction to the music.

Likewise, the second motive looks quite similar:

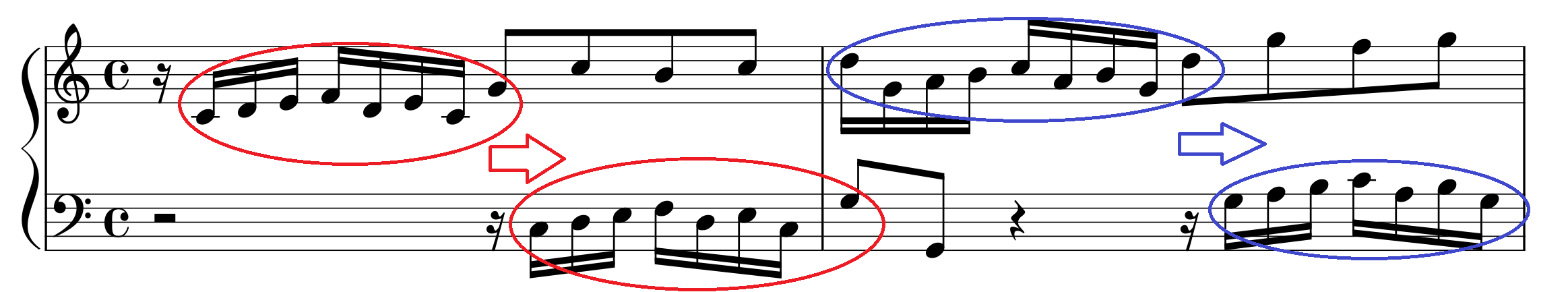

Imitation

I also notice a couple instances of imitation.

I could diagram them as follows:

Do you see how “imitation” is simply one thing followed by another? First, you do the first thing. Then, you do the second, in response.

Sequences

Sequences are rather similar. They are chains of events. Starting at measure 3, we see one, with each event outlined in red.

Thinking of the sequence as a chain of beat-structures, we could diagram it like this:

Starting at measure 9 is another sequence, which I have chosen to diagram as follows.

At the risk of repeating myself, there is no right or wrong here. I must emphasize that this is not intended to be a scholarly analysis of Bach’s music, but rather an explanation of how I saw it, in the moment that I made these diagrams and wrote this text.

Implied Voices

Finally, the very end of the piece has some interesting implied voices I want to bring out. This is a 2-part invention, but I see four voices at the end. In truth, Bach’s 2-part music always has more than two voices, and if I go hunting, I’ll find more. This must also be understood in terms of beats, and the video illustrates how I do this. I want to point out that working this way completely eliminates any need to struggle with finger independence when playing Bach. You will develop complete and total control over all voices, limited only by your imagination.

5. Map out the harmony.

My whole strategy is to start observing basic elements, and gradually look for refinements as I feel the need. In essence, I am only categorizing what I observe. Let me repeat that there is no right or wrong.

Let’s look deeper into harmony. Ideally, I would have an understanding of every single symbol on the page, and an understanding of every relationship between every symbol on the page. That’s a lot of information to process. We can start digging deeper by looking at accidentals, and getting a sense about why Bach wrote them. I go through each one, come up with a rationale, and play that passage, observing how it impacts the music.

Example:

My rationales are quick judgments. If I spent more time on them, they might reveal deeper patterns. It doesn’t really matter. What’s important is that your analysis of the music is convincing to you. If you find that your analysis doesn’t work for some other purpose, you can always change it when you get to that point.

Let’s look at the accidentals, which will expose more interesting patterns in the harmony.

The harmonies are events, and they are regulated by beats, as all musical events are. My task is to see the music this way. If I look at the phrase starting at measure 3, I could diagram it as a sequence of harmonies. I use Roman numerals to designate the harmonies, but the notation is not important. What is important is that this phrase is a sequence of harmonic events, one leading into the next. I want to understand how that is organized, so that it makes sense intuitively.

Examples of harmonic features:

No need to understand these completely, but I wanted to show the types of observations I make when looking at a score:

- Measure 4: one F# in the left hand, and another in the right hand, suggesting the key of G. The key is reinforced several times.

- Measure 9: the F# returns to an F natural, implying a return to the key of C. Thus, the left hand F resolves to an E in measure 10.

- The C# in measure 10 indicates D minor, as does the B-flat. Notice the B-flat leading down to F.

- The B natural means we’re back in C major, with a V7 chord here.

- Measure 12 has an F# and G# leading to an A, and this, combined with the C natural, suggests A minor.

- So, the D in measure 13 is a suspension resolving to the C.

- G# in this section is always the leading tone.

- Measure 15: the G# reverts to G natural, and the C# means D minor.

- The C natural in measure 16 suggests the key of C, and there’s a V7 chord here.

- Thus, the F in measure 17 is a suspension, resolving to E in measure 18.

- The B-flat in measure 18 is from the key of F, suggesting a new idea here. Note the progression from vi6 to i6 over the next couple measures.

- Return to the key of C in measure 20 with the B natural, reinforced by the right hand melody.

- Measure 21 starts with the end of a progression ending on I6, quickly returning to the key of F with the B-flat.

- The B natural indicates a return to the key of C.

- Notice the progression here of IV-V7-I.

Video demonstration

In the video, I play through a couple of these phrases, setting the beat to various note values, so that I can observe the harmonic rhythm on different levels. Again, it’s not about expression, and not about programming muscle memory to play dynamics properly. It’s about observation.

6. Put it all together.

Having done all of this, I play through the piece twice. The video is intended to illustrate how my analytical understanding of the music comes through when I simply sit down and tell myself to play. If it doesn’t come through, chances are I am either not completely focusing on the music, or the ways in which my body expresses my musical ideas are not quite effective enough. These are topics which will have to be dealt with in another article.

Example:

This video is not meant to demonstrate a perfect performance of this piece. My focus here is on the process, not the outcome. If I want a more perfect performance, I would spend more time on this process, clarifying the musical ideas down to the smallest detail, if necessary (actually, I would probably leave that task to a performer who has more patience than I do), and I would spend more time challenging my focus levels, to ensure that I could concentrate on my musical concept no matter what else was going on.

What about…?

There are some aspects of music that I’m not including in my analysis:

Dynamics

I generally do not pay much attention to dynamics in my analysis of the music, unless I can see that the composer made a special point of indicating a specific dynamic marking. Dynamics are perhaps better understood as a feature of harmony. They are usually intimately related to the structure of the phrase, and when you understand the phrase, the dynamics happen automatically. Let yourself respond to the music. Rather than thinking in terms of “loud” and “soft”, it is better to think in terms of “tension”, “resolution”, and “energy”. But don’t plan it out. Understand the mechanics of the phrase, and the dynamics must happen.

Emotions

Your job is not to express emotion. You are expressing emotion, 24 hours a day. Rather, your job is to understand the piece in a way that is coherent, and to stay focused while you perform the piece.

Play the music, not the analysis, and the emotions you experience while you play will come through. You can’t control them, or rely on the fact that they will come back next time. Simply play the music. You will react to it, based on your understanding of what you are reacting to, and the fact that you are a human being who responds to music. Your technical practice must be mechanical. Do not let emotion interfere with it.

Two types of piano players:

Players fall into one of two extremes here. Either they are too technical, or they are too emotional. Many teachers don’t understand the difference. Players who are too emotional have allowed their emotions to influence their practicing in a way that doesn’t work during performance. Often, they can play well when they are in a room alone, but onstage they experience so much anxiety that nothing works. Their playing may seem uninvolved, because they aren’t correctly executing the musical ideas, but really the problem is that they are too involved.

Technical players have the opposite problem. Playing is too easy for them, and thus they can perform difficult works without having to understand the music. What they are lacking is analysis, and this is why their playing doesn’t sound like music.

Players can have both problems simultaneously. For example, it is possible to have severe stage fright, and also not understand the music you are playing.

Don’t let either of these stop you from practicing technically, or from investing in the moment. You need to understand the music mechanically, devoid of emotion, so that you are free to put true emotion into it in the moment of performance. It must be easy to play, so that you can react to it as an observer.

Many teachers even encourage always practicing with extreme emotion, as it aids in memory. It does indeed aid in memory, and for this reason I believe it’s a mistake. The problem is that in a performance, you may not be in control of your emotions, and if a given emotional state is required to recall something from memory, you may be out of luck.

Your turn

I hope you can see that my method of analysis always aims to be exceedingly simple, based only on the music. It does not require an extensive background in music theory, although the more knowledge you have, the better. Instead, it relies only on breaking the music down into the simplest possible pieces, and structuring them in a way that makes sense to you. When you perform, you will be delivering an interpretation that is uniquely yours, and thus hopefully satisfying to you. If you see less than I do, ignore the parts you don’t see. Maybe I’m imagining them, anyway!

Do not hold yourself accountable for that which you do not see. My analysis of this music was done in a matter of minutes. If you want to spend hours, or weeks on it, go ahead. You will possibly see more than I saw, and your performance will reflect that. But, don’t insist you are playing it wrong because you just know there’s something you aren’t seeing, even if you can’t put your finger on what exactly it is. Make a decision, and play it. Your performance is always perfect, in that it is a direct result of both your current level of understanding, and exactly what you are doing in the moment.

Comments

One response to “Music Analysis for Pianists”

[…] couple years ago, I wrote a blog post about music theory. I analyzed a Bach Invention and included a video […]