Out of all of the skills related to piano, sight reading can be one of the most frustrating. Wouldn’t it be great if you could sight-read anything? Imagine that you could:

- Play all the right notes and rhythms.

- Sight-read at any tempo, fast or slow.

- Feel calm and relaxed as you sight-read.

- Sight-read in a way that sounds and flows like real music.

In this article, I will list several habits that pianists frequently have, which actually make it harder to learn to sight-read anything. I hope you find this collection of piano sight-reading tips useful in your own practice.

Get my e-book

I wrote this ebook because I want to share what I’ve learned about what’s wrong with the way the piano community treats “amateur” pianists. I don’t like it, and I want to change it.

It is rare to see something written for serious adult amateurs, and by someone who went that route. I had it on as an audiobook while doing chores – the first chapter on various aspects regarding teachers, I was saying “right” and “certainly” out loud a few times. 😀 A lot of the things, I wished I’d heard this when I first started my first ever lessons some time ago; it took me years to at least partly find my way out of holes due to some of those things.

Inge

Amateur Pianist

Bad Habit 1:

You make sight-reading difficult

When you practice sight-reading on the piano, you fix your eyes on the music and struggle to get through.

Many pianists have trouble understanding how to get better at sight-reading with ease. This is because they don’t make ease a priority. While sight-reading, you might find that:

- Just looking at a complex score makes you feel confused and stressed.

- Sight-reading at an uncomfortable tempo (either too fast or too slow!) makes you feel nervous.

- You feel pain or fatigue.

- You can’t really feel the music.

This is often a sign that you aren’t making ease a priority.

What to do instead:

Remind yourself that music is supposed to be fun and that you can’t do better than your best. Pay attention to how things feel, not just whether you’re playing the right notes. When you look at a complicated score, view it like you would a map of a city. You don’t have to understand everything all at once.

Bad Habit 2:

You’re not coordinated when you sight-read at the piano

Your eyes move frantically up and down between the music and the keyboard. Your hands jerk around randomly as you struggle to find the right notes.

Our education system teaches us to view things in black and white terms. In order to get a passing grade, we learn to do what is right and avoid what is wrong. When we take music lessons, we carry this attitude into our practicing. Through no fault of our own, we can end up viewing music reading in the same light as math or physics. This can have the effect of causing us to detach emotionally from the task, making things feel difficult and tiresome. Thus, for completely understandable reasons, many students totally ignore their musicality when reading.

Furthermore, sight-reading is hard! As with all things piano, sight-reading asks us to bring our complete selves to the table. Our minds and our bodies must work in harmony to allow us to function as a unified whole. Specifically, you must coordinate:

- Your eyes

- The parts of your body that are directly involved in playing the instrument

- The rest of your body

- The instrument itself

- The page turns

What’s more, all of these must be coordinated with the beat, the musical intention, the conductor, the singer, etc.

Once you come to terms with all of this, you will know how to get better at sight-reading.

What to do instead:

Let your body do what it needs to do. If your eyes want to move up and down, let them, but also encourage them to stay in one place long enough to feel the stress that comes from not knowing if you’re going to play the next note correctly.

When you turn a page, do it in tempo. Page turns are part of the music as well.

Bad Habit 3:

You’re not reading the score the right way

When you read music, you try to play everything exactly as it is written, no matter what. If you hit a wrong note, you stop and make sure you hit the right one before going on.

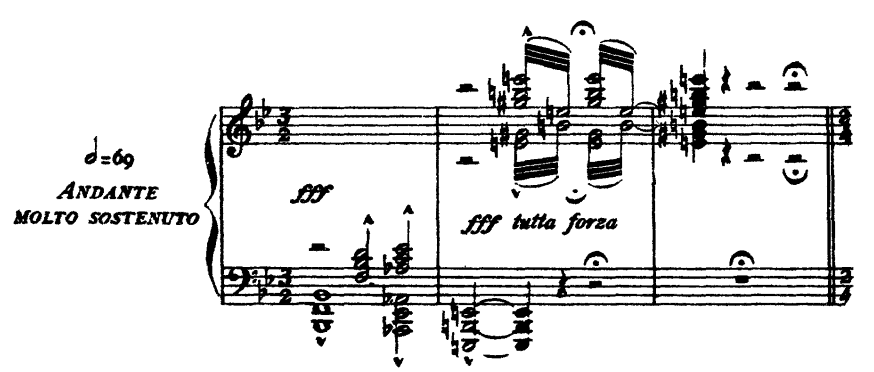

If you wish to improve your piano sight-reading, your task is to understand how to read a score, so that you can extract all of the relevant details. That is, you are learning how to connect to the composer’s intention by absorbing this picture. You want to be able to extract as many of them as you possibly can, in real-time. In the end, you want to be able to do this quickly, allowing the music to simply flow off of the page and through your body.

What is a musical score?

A visual representation of how the composer wants the music to sound. It’s more of a picture, or an outline, than a step-by-step recipe.

A description of the beats of music. (What pitches occur on each beat? How are the beats grouped into meter? What happens between the beats?)

An outline which marks the basic events occurring in the piece (repeats, phrases, accents, crescendos, fermatas, etc.)

The score is not the music. It’s a picture of the music. Additionally, It is not, strictly speaking, a set of instructions for how to play (even though it may have some instructions in it).

What to do instead:

Remind yourself that you are making music, not following instructions. Do not stop to correct wrong notes. This is not correct, even if it’s what it says in the score, because “corrections” are not part of actual music!

Bad Habit 4:

You aren’t deciding what’s important

You treat every detail in the score equally. Notes are just as important to you as rhythms, and articulations are just as important as dynamics.

- You often do not have time to absorb all of the details on the page. What you do absorb should be more important than what you don’t absorb.

- Your entire physical state must give preference to the important elements. For example, if your body is not generally “moving to the beat”, you will find it difficult to articulate the fingers properly.

- Thinking hierarchically makes it easier to understand what you are reading. For example, when you read a novel, it is useful to understand how the text is broken into paragraphs, words, sentences, chapters, etc., as this improves comprehension.

- With improved comprehension comes greater room for creativity. When you understand the basic building blocks in front of you, you can then assemble them in the order that makes the most sense to you.

- With creativity comes a more engaged performance. As a result, you will enjoy yourself more, and the audience will enjoy the performance more as well.

What to do instead:

There must be a hierarchy to what appears in the score. What this means is that the elements higher up the hierarchy are more important than the ones further down. For this reason, a big part of your artistry is determining what you wish this hierarchy to be. However, it may vary from piece to piece.

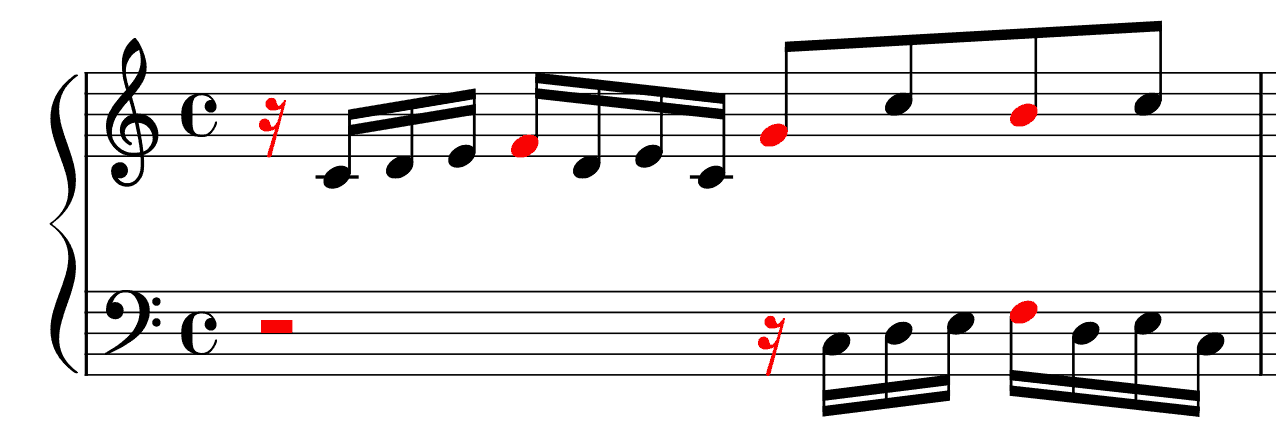

As an example, in order of most to least important:

Beat and meter

Phrases and cadences

Rhythm

Pitch

Counterpoint

I often think of music in this way, but there is space for individual variation and creativity. By focusing on the aspects of music that you find important, you will be able to read a piece in a way that is meaningful to you.

Bad Habit 5:

You aren’t practicing well

For example:

- When there is a trouble spot, you stop and figure it out before moving on. When things are easier, increase the tempo.

- You deliberately read 1 or 2 measures ahead of where you’re playing

- You let yourself “stutter” and “hunt around” for the notes as you play.

When I learned to sight-read, I did not follow any formal strategies or use any “tricks”. Nonetheless, it took me less than a year after I began studying piano before I was what I would call “reasonably fluent” at reading both hands together. I am not saying this to brag, but to make the point that if you want to improve your sight-reading skills quickly, you can. I attribute my progress to the fact that I simply read a ton of music, without fear of making mistakes.

What to do instead:

Let me offer this basic method to get better at sight-reading:

Decide what note gets the beat, and what basic physical action you will use to perform these beats.

Choose a tempo and stick to it. Use a metronome.

Decide on what is important, and what isn’t. When you play, prioritize what is important.

Keeping your eyes on the music, play from the beginning to the end, without stopping. Try not to look at your hands (but it’s no big deal if you do).

This is the basic formula, and you can vary it as needed. For example:

Change what you are prioritizing. For example, you may prioritize the bass line or one of the inner voices.

Change which durations you are playing. You may decide only to play the notes that fall on the quarter note beat, for example. Alternatively, you might play just the downbeat of each measure.

Play easier music, or harder music.

Play faster, or slower.

Let yourself feel the beat as you read.

Try to make music.

Play the piece as you feel it should sound, even if it doesn’t come out exactly right.

Even if you don’t know the piece very well, you have the right to your interpretation. Trust your inner self to know what to do.

Try playing both hands, or at a tempo that feels a little too fast for you. Try to ease into this difficulty, noticing how your body wants to react.

Do not write in the pitches.

Understanding music theory can be somewhat helpful, but it is not the most important thing. You will recognize chords mostly by their shapes, not as much by their harmonic functions. However, you should be comfortable playing scales in the key signature that the piece is in. If you are trying to read accidentals while sight-reading at the piano, this will generally throw a wrench in the works.

Bad Habit 6:

You don’t play confidently and securely

If the music is too hard for you, you slow it down. When it gets easy, you speed back up. After each note, you check to make sure it’s right before moving on.

When you practice playing timidly and hesitantly, you will ingrain that way of playing into your system. This will not lead to confident music-making any time soon. Music that has constant stops and starts, or constant tempo fluctuations, does not sound like music. You don’t want to get into the habit of playing that way.

What to do instead:

If you don’t feel comfortable playing fast, then play slower. But, always play confidently and securely. Every beat that you play must be decisive and sure. Then, you go to the next beat and play that one as confidently as the previous one. Over time, you can then work on lining up your beats in tempo. Whatever you do, do not “stutter“.

Bad Habit 7:

You aren’t keeping a steady beat

You get stressed out by complicated-looking rhythms and let them interfere with the pulse of the music.

The rhythms will come eventually, once you learn to recognize the patterns. However, you will never be perfect at recognizing rhythms at sight. Music notation can, at times, be too confusing for this to work.

So, do not let the rhythms interfere with the beat. The beat is the most important thing. Listeners will generally never mind an incorrect rhythm, but a missed beat is immediately noticeable.

What to do instead:

Keep a steady beat. This is the most important thing, always.

Focus on getting the correct notes that fall on the beats. Do not worry about the notes that fall in between beats.

Bad Habit 8:

You don’t like the way you practice sight-reading

Practicing sight-reading feels like a drag, and you have to force yourself to do it.

As far as practice goes, the more you practice, the easier piano sight-reading will become. However, if your experience practicing sight-reading is less than exciting and engaging, you will not be motivated to do it. Pay attention to what encourages you to practice, and also to what discourages you.

What might be stopping you from reading a lot:

Perfectionistic attitudes about correctness.

An approach to reading that causes physical discomfort.

A sense that you are “bad at this”, and have a huge deficiency to overcome.

Judgment from others about how good your reading is.

Reading music you dislike.

A busy schedule that limits practice time.

Tension and fatigue in your body.

A history of having difficulties in sight-reading and either being hard on yourself or being judged by others.

If any of this applies to you, you should find ways of practicing that are more fun for you.

What to do instead:

You might try the following strategies:

Reading music you enjoy listening to.

Setting a goal such as “read through all the Mozart sonatas this weekend”, and just plowing through it.

Ignoring all of your mistakes (if you hate fixing mistakes).

Spending time diligently correcting all your mistakes (if you love fixing mistakes).

Focusing on physical sensation rather than correctness. Paying more attention to the feeling of the music, and the feeling of your body playing the instrument, rather than whether or not you are playing correctly.

Playing duets, chamber music, vocal music, etc.

Reading the easier parts and ignoring the harder parts.

Play with freedom like you did as a child. Ignore the hard parts!

Bad Habit 9:

You don’t sight-read enough music

You sight-read one line of music a day, or you only sight-read when you first play a new piece you’re planning on memorizing.

Surprisingly, sight-reading is closely related to memory. Pieces that are similar to pieces you already know are easier to read. This is because reading is basically pattern recognition. If you are not good at sight-reading, your priority must be reading lots and lots of music, so that your brain can collect a large number of patterns.

Therefore, the more pieces you read, the better you will get at reading new pieces (especially those in the style of the music you are already familiar with). When I was learning to play the piano, I read a ton of music. Everything I could get my hands on. This paid off, big time.

What to do instead:

Your sight-reading will only improve if you treat it like anything else in piano. Sight-reading takes practice: a lot of it. You must spend many, many hours sight-reading, and make tons of mistakes. That’s how you learn. So, play lots of music:

You can try sight-reading exercises if you find them useful.

Play music that is too easy, and also music that is too hard.

- Play music that is contrapuntal. Bach is always great for sight-reading. Play music that has 4-part harmony, such as in a hymnal. Train yourself to focus on the parts individually while you play. Start with just one part at a time.

- Play music that is in the style in which you want to improve your sight-reading.

You should play music that is of interest to you. Then, you will be more motivated to read it.

How to Improve Sight-Reading at the Piano

Generally, anything that gets you to read a lot is a good way to practice, and anything that prevents you from reading a lot is not.

Increase the conditions that lead to more sight-reading. Work on eradicating whatever’s getting in your way. With practice, your sight-reading will improve.

Practice everyday. Set a timer, if you need to. If you skip a day or two, do not beat yourself up about it.

If you find yourself getting discouraged, pay attention to what is causing the discouragement. Focus more on what you find motivating. Remember that practicing is about you.

Anyone can learn how to improve their piano sight-reading. There is no magic bullet here. Basically, you just need to read a lot. The suggestions I’ve given here aimed at making it more fun and engaging for you to read so that you will be more likely to do it, and so that you will pay more attention while you are doing it.

Your turn

Are there any other habits you have noticed that you have while sight-reading? Any other sight-reading tips for pianists, which you have found useful?

I’m curious to know what has worked for you, and what has gotten in the way. Leave a comment below and let me know!

Comments

3 responses to “9 Piano Sight-Reading Habits That You Should Stop Doing”

Encouraging post, thank you. I’ve been keeping sight reading interesting by cycling through a handful of methods every couple of weeks: sightreadingfactory.com, sightreading.training, pianomarvel.com and the Paul Harris books.

Yeah, totally, you gotta throw a whole bunch of stuff at it and see what sticks. No sense in limiting yourself to one rigid way of doing things. Music is a language and you learn to read it by reading it and getting used to it. DM me on Instagram if you want to chat more (@no.michael.here).

Thanks for your tips. The message I’m getting is this: Just Relax… it’s not so difficult, have fun and practice a lot- Improvement will come!

I’ve played piano by ear for decades but as a child was extremely resistant to learning sheet. I developed my note reading and chords after a few years but never got the hang of deciphering rhythms. Would be nice.