Solving your hand independence problem takes willingness to get a little bit uncomfortable. You’ve got to allow things to get mentally awkward. To give up your rigid need for control.

Some pianists (“snowflake pianists”), simply can’t deal with the fact that their hands don’t feel independent of each other. They generally quit piano soon enough, but some of them go on to become advanced.

Get my e-book

I wrote this ebook because I want to share what I’ve learned about what’s wrong with the way the piano community treats “amateur” pianists. I don’t like it, and I want to change it.

It is rare to see something written for serious adult amateurs, and by someone who went that route. I had it on as an audiobook while doing chores – the first chapter on various aspects regarding teachers, I was saying “right” and “certainly” out loud a few times. 😀 A lot of the things, I wished I’d heard this when I first started my first ever lessons some time ago; it took me years to at least partly find my way out of holes due to some of those things.

Inge

Amateur Pianist

Even the advanced ones still struggle with basic stuff like:

Yeah, I get it. Figuring out how to play the piano with two hands doing different things is not always obvious. Most people are born with two hands, and we are not supposed to get overwhelmed using both of them. Sit down in front of a piano, and it stops feeling natural.

In this article, I’ll give you some tips that will help you conquer this problem. It will take practice, of course, but if you know where to direct your efforts, you’ll quickly start untying knots.

(At least I’ll be able to tell the “snowflake pianists” I tried…)

Tip 1: Deliberately decide to work on hand independence

With the right kind of practice, you can solve these problems. So, before you expect any results, you must make a decision to practice hand independence.

If you don’t make this decision, then your practicing will be aimless.

However, if you make a decision to work on hand independence, then you’ll be able to evaluate your practicing, and determine whether or not it’s working. That’s a good spot to be in, because then you can do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

How to begin practicing hand independence:

Before you sit down to practice, remind yourself why you’re doing it. Write it down. Say it out loud:

“I am practicing today because I want to learn how to develop hand independence.”

Most pianists overlook this important step. Big mistake.

Tip 2: Stop trying “shortcuts” that don’t work

When we don’t get the results want, we try all sorts of things out of desperation. This wastes valuable time and energy, and makes us confused.

Many pianists will try shortcuts such as:

- Strengthening their fingers.

- Stretching their fingers.

- Trying harder.

If your left hand feels weaker than your right hand, you don’t need to strengthen your left hand. It’s about coordination, not strength, even if it “feels” weak (think about how weak your arms feel trying to lift a heavy box when you don’t first have a solid footing).

When the hands don’t seem equal or independent, it can even seem like there’s a physical problem. But, unless you have an injury or unusual anatomy, I doubt it’s a physical problem.

Instead, realize that it’s a mental problem. Trying really hard is not necessary. Watch some great pianists on YouTube. They are not struggling, not trying hard. That’s because their coordination is good, not because they spent time strengthening their finger muscles.

How to be more patient with yourself as you learn hand independence at the piano

When you feel impatient, try to notice what you do to rush the process along. Remind yourself that there are no shortcuts and stop doing those things. You’re wasting your time and barking up the wrong tree.

In the meantime, try to pay attention to aspects of your practicing that you are enjoying. When we fixate on what results we’re not getting, practicing stops being fun, and we stop doing it.

Tip 3: Slow down and pay attention

Go at the pace your body requires.

Why is it so hard to play the piano with both hands? Like I said earlier, because you’re impatient. When you don’t let your mind and body dictate the pace, you get a traffic jam in your brain.

This means you need to slow down and pay attention. Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes for sorting this out. That’s just not how it works. You must figure it out on your own.

You might not know right away exactly why your right hand feels better than your left. But, if you persist with patience and awareness, you will eventually learn. It just takes time.

This means that practicing piano is meditation. There’s no way around it. And, I’m talking about hardcore meditation, not the hippie version with crystals and incense.

How to slow down and pay attention:

When we are frustrated that our body isn’t doing what we want it to be doing, we tend to do two things: (1) speed up, and (2) stop paying attention. To gain better hand independence at the piano, we have to do the opposite of those.

The key is in noticing when they start to happen. Pay attention to the feeling of the frustration. You want to view the frustration as a good thing. If you can do this, you won’t see any need to speed up or stop paying attention. (This is weird, but you can learn it through meditation).

The frustration is good. It means that you care about getting good results at the piano. But, frustration makes learning harder.

So, stop fighting the frustration. It will make learning easier.

Tip 4: Unify the body

Feel the beat in the whole body. Play both hands as one.

When you start paying attention with mindfulness, you realize something surprising: you don’t need to have complete hand independence to play the piano.

Both hands actually always do the same thing. In piano playing, your hands cannot move totally independently. After all, the body connects them together.

Imagine you’re walking. Both feet move “independently”, and yet the whole body moves in one direction. It would be a big mistake to have your left foot moving in one direction and the right moving in another.

Piano works the same way. The whole body plays the whole piece of music. Both hands move to the same beat. As in walking, it’s a mistake to try to keep everything independent. Instead, aim for unity.

Another example: Imagine yourself walking and texting on your phone at the same time. Notice how the movements of your feet will influence the movements that you use for texting. Also notice how texting while walking will feel subtly different than texting while sitting. Let those differences happen, and don’t try to fight them.

How to unify the body

Here is an exercise you can try. Play a piece with both hands, but only play the notes that land on the beats. This will encourage you to focus on the beat, and the beat will be the same in both hands.

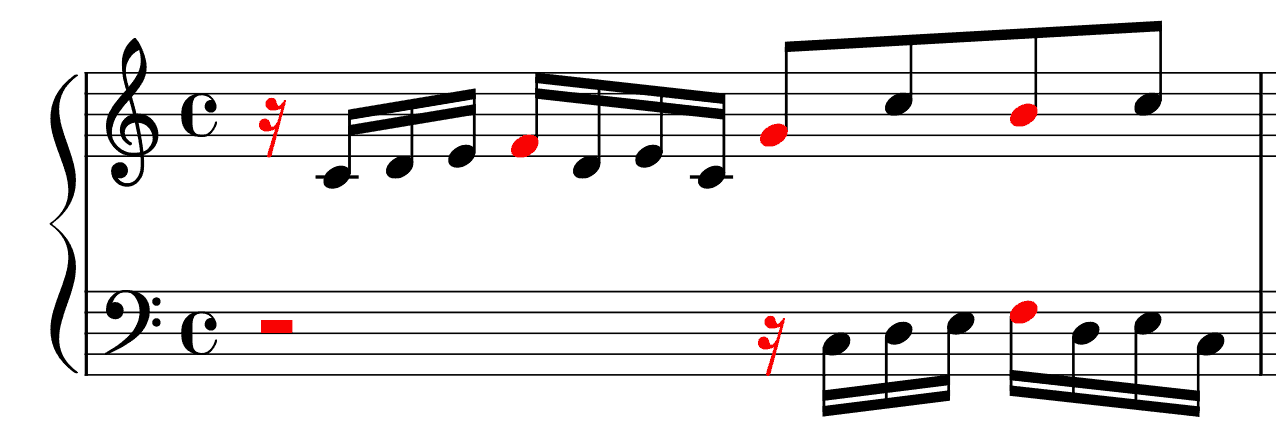

Play only the notes in red. Each one is a full-body action, both hands together. Use a metronome to force you to focus on the movement that happens on the beat.

Tip 5: Prioritize what’s important

Make a decision about what is important to you when you play, and don’t let the notes distract you from that.

Suppose you are walking with a friend and you have an itch on your face. You will not stop walking to scratch the itch. You will keep walking, because you don’t want to get behind your friend, or make your friend wait for you. The walking is more important than the scratching. Because you have set your priorities, there is no problem doing both at the same time.

When you play the piano, don’t let a difficult spot in one hand throw off the entire rhythm of the music. (That’s why it feels difficult to play the piano with both hands.)

Set a priority for yourself which is as easy as walking, and let the little details will take care of themselves.

Getting started with priority-setting

To try this out, pick something that is really easy. For example, you can say “my priority is to make it to the end of the piece.” Then, try playing the piece. You are free to make any mistakes you want, but at least get to the end.

While you’re playing, you might find that your hands get tangled up. That’s fine. The rules do not say that you need to play all the notes correctly, only that you need to get to the end.

Here are some other examples of priorities:

- Play softly

- Bring out the melody in the right hand

- Keep a steady beat

These priorities will take your focus off of hand independence while you play the piano, and put it on something you have more control over.

Tip 6: Explore the body

Instead of focusing only on the fact that your hands are getting tangled up, dig deeper into the body.

In a passage where one hand seems to be written slower than the other, remember that neither is ever actually slower. The tempo is still the same in both hands. Feel this energy balanced throughout the body. There must be an constant, internal pulse that governs both hands.

When you can feel how your whole body responds to this pulse, it will be much easier to notice what causes problems. Remember that the body is a physical thing. It has mass, and is governed by the laws of motion. You must learn to respect this.

How to get started exploring the body

Start by exploring your instincts around the relationship between your hands. Notice what it feels like to move your torso around, and how that affects what your hands are doing. Do things feel independent, or do they feel tightly wound up?

Play hands in parallel motion and contrary motion, and notice what happens. What does it feel like? Does one feel easier than the other? Does one hand feel better going in a certain direction?

Play passages where one hand moves and the other doesn’t. Notice where you feel stuck or where you feel one hand trying to “pull” on the other.

Tip 7: Feel the beat

Instead of looking for “hand independence exercises,” take the opportunity to make any piano piece into an exercise to coordinate the left and right hand.

A piece of music should have a steady beat. When the beat is not steady, you feel it, and the audience will hear it. So, this should always be your top priority.

How to feel the beat:

Always, start by making sure both hands are “doing the same thing.” That is, ensure that both hands are playing at the same time. Use a metronome, if necessary. You should feel the beat throughout your entire body. This is the essential first step in training your hands for piano.

Once you’ve got the beat established, work on differentiating the hands. This means add the smaller details.

You may find yourself getting stuck again, like your hands are not cooperating. Or, perhaps it’s just one hand that’s not cooperating. In either case, go back to making sure that the beat is consistent between both hands.

Tip 8: Read hands together

Instead of thinking of music as having a right hand plus a left hand, think of both hands together. Even when you’re reading a piece for the first time!

Sight-reading always screws up the coordination between the hands for some pianists. Maybe you can read each hand independently with no problem, but putting them together causes everything to slow down. Or, one hand is fine, but the other isn’t.

Remember that both hands must always move at the same time. It’s paradoxical, but this is how you actually achieve hand independence in piano playing. You cannot let one hand get ahead of the other. If treble clef is easier for you than bass clef, your right hand might get impatient waiting for your left. You, however, must wait patiently for both hands to be ready. If you can’t do this you should ask yourself why. Where are you in a hurry to go?

When you are reading, your brain must process each beat before playing it. You can’t think of each hand separately, and move each hand separately. The entire beat (left hand plus right hand) is one action. It should all be comfortable, and it should all make sense to you.

How to sight-read both hands:

When you sight-read a new piece, make a resolution to play both hands. Try to zoom out a little bit and see both hands at once. Even if you make a mistake, keep going.

Set your priorities. Decide which musical elements are the most important ones. Let your whole body play those elements. Don’t get trapped into thinking that you need to play everything on the page. Remember that it must all fit into the structure of your body.

This takes practice to do perfectly. But if you persist, you will make progress.

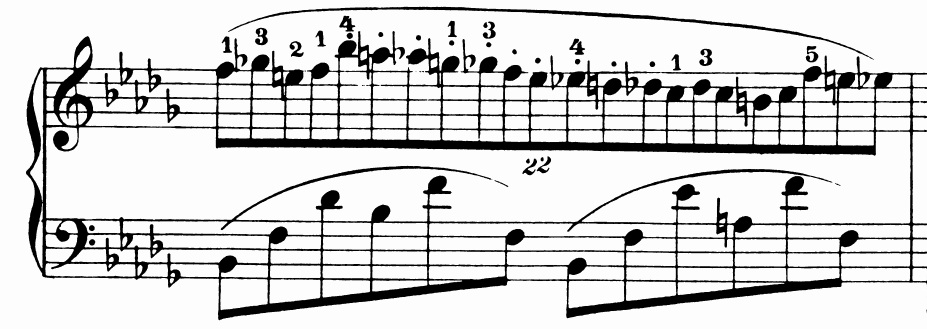

Tip 9: Play Bach

Try practicing Bach preludes, inventions, and fugues.

Bach’s music will challenge your finger independence as well as your hand independence. Contrary to popular opinion, it does not need flexible or strong fingers. The challenge is all in your mind.

Finger independence is basically the same issue as hand independence. Here, the whole hand must be unified. Even if the five fingers are playing different things, the hand as a whole is moving in one direction.

How to approach Bach for hand independence:

First, you should understand that Bach’s music generally consists of multiple simultaneous voices. Do you see that in the music? Can you hear it when you listen to a recording?

As a pianist, it’s your job to express all of these voices at the same time. This is a really hard thing to do! However, with a lot of patience, you can master this skill. Don’t expect perfection at first.

Play through a Bach piece, and try to mentally follow one voice at a time, from beginning to end. You can try singing along. Then, do it with another voice.

The whole aim here is to untangle yourself mentally. The physical stuff will follow from that.

Tip 10: Mix up the dynamics

Many pianists have a hard time playing different dynamics between the two hands. This is an essential skill, and if you struggle with it, you should make this a priority.

As always, the beat needs to be the same in both hands. This is usually the problem (and fixing it is usually the solution…). If you have no unified sense of beat, it’s like you’re trying to micromanage each hand separately. This just overloads the brain.

If you can play each hand at a different dynamic level, you will have significantly more control.

Playing different dynamics in each hand

First ensure that both hands can play together with no problem.

Next, experiment with “LH soft + RH loud”. You should think of this as a single action. If you find that doing this messes up your beat, you are not thinking of it as a single action.

Likewise, experiment with “LH loud + RH soft”.

Tip 11: Mix up the articulation

Practice playing legato in one hand and staccato in the other.

As with dynamics, this will help you attain significantly greater control. It will make it much easier to play music like Bach, where this level of control is required.

The Solution:

See the previous tip about dynamics. The concept is the same. You want to think of both hands as playing together. It’s just that one of them is legato, and the other is staccato.

Tip 12: Let the notes fall where they need to

If you are playing a piece with polyrhythms, such as 3 against 2, or 11 against 7, or 25 against 8, or whatever, do not attempt to calculate mathematically how the notes should line up. Instead, decide where the beats are, and make sure that both hands are playing the beats at the same time. Let the other notes fall where they need to.

The composer probably did not intend for you to count things precisely, anyway.

If one hand has 25 notes, and the other has 3, they are both playing at the same tempo. Sure, one has more notes, but the metronome clicks the same regardless. Feel the metronome in your body, not the notes.

How to let the notes fall where they need to

When you see a difficult rhythmic figure, try to get a sense of the overall shape of the thing. Then, when you play, make sure that you can:

- play the first note correctly, and

- keep a steady beat.

For now, don’t worry about the other notes. Take your best guess, but don’t interrupt the flow. This is harder than it sounds, but it’s worth the practice.

Be patient

As with everything at the piano, hand independence is easy to fix if you practice the right way. Be patient with yourself, and with your body. When you let things happen as they must happen, you’ll see how to get out of your own way.

It’s worth it, by the way. If you learn to play comfortably with both hands, you can expect the following benefits:

Remember, this isn’t a physical problem. It’s is a problem you can solve with the right kind of mindful practice.

Are you interested in learning more about how mindfulness can help you with piano playing? Check out my Five-Dollar Piano Lesson.

Leave a Reply